Three Profiles in Spirit & Kindness in Old Age

Or, How to Be Kind Even When You've Lost Your Mind

The last newsletter I sent out was about how misunderstanding certain aspects of Zen training can make you a jerk. It seems to have struck a nerve (in a good way).

Thank you to everyone for liking and sharing it. Welcome also to everyone who is new to the list, including those who joined as paid subscribers, a Substack feature I've just turned on.

I thought it appropriate to follow up with a salve of sorts, a reassuring reminder that there is a reason to train in spiritual discipline and put in all the effort to develop ourselves despite the potential pitfalls.

My premise today is that spiritual training can refine us to the point that we can be kind in this life and bring light to the world as long as we live. Even when we are tired and in pain. Even when we're struggling and suffering, or simply old enough to be irreversibly set in our ways. And even when our bodies and our minds are decrepit.

Spiritual training can refine us to the point that we can be kind in this life and bring light to the world as long as we live. Even when we are tired and in pain. And even when our bodies and our minds are decrepit.

Below are glimpses at three different people who found ways to train their bodies, minds, and spirits so deeply that, in their old age, they seem effortlessly kind and welcoming. They are not the curmudgeonly old men yelling "Get off my lawn!" They are joys to be around and bring happiness wherever they go, much like how babies light up a room just by the force of who and what they are. These men are the shining examples at the end of what can sometimes feel like a long, dark tunnel of spiritual effort, inspiration for us all to keep training.

Tom Morelli

When I first arrived at Chozen-ji—the Rinzai Zen temple and Dojo in Hawaii where I live and train—one of the first Dojo members I met was an old Zen priest named Tom.

Tom had trained for decades at Chozen-ji, though it had been some time since he'd been active. Then in his late 70s and in poor health, he showed up at the Dojo with the assistance of his son, Tommy. He labored to get up and down the few steps into the main Dojo and, when it came time to sit and talk story in the air conditioning for a while, I pulled out a chair for him, knowing that sitting on the floor, as we usually do, was asking too much.

When we first met, Tom's eyes lit up as I responded to his questions as to who I was and when I had arrived at Chozen-ji.

"Are you going to stay long?" he also asked, to which I responded that I had recently told the Abbot I wanted to live in long term, so yes, I'd be here for as long as they'd have me! We shared a laugh at that and he expressed his pleasure about people continuing to do the rigorous, physical Zen training through meditation, and the martial and fine arts for which our Dojo was known.

"That's wonderful," Tom said, tired from the hot Hawaiian sun, but evidently content. "That's wonderful," he said again for emphasis.

Michael, the resident priest, told Tom about what we were working on at the Dojo—about the new classes being started and the new students who were enrolling, reinvigorating the training after a spell of hibernal quiet at the Dojo that had lasted many years.

"How does it feel?" Michael asked.

"Well," Tom responded, "the kiai is different." (Kiai is a Japanese word that can be translated as energy, vibration, or feeling; and developing one's kiai is a cornerstone of Chozen-ji training.)

"Tom, can you describe how it's changed?" I asked. The Dojo now was all I had ever known and I struggled to imagine it otherwise.

"Well," he said, "it feels alive," Tom said.

Suddenly and with apparent surprise at his own words, Tom began to sob. My eyes, too, welled with tears.

Even though I had only been at Chozen-ji a few months, I understood what a precious and unique place this was. It was worth committing to stay here long term—even indefinitely, even after my interesting, exciting, and international life. The training and the community struck me as everything I had been looking for, even if I hadn't known I was looking for it.

"It means so much to hear you say that, Tom," I said. "It makes me want to train hard."

A few minutes passed and we decided to get some air and walk down the path. We said we'd go back to the founder's memorial to pay our respects to "Roshi". Michael, who had had to step away for a few minutes, now walked back up the path in our direction.

"Hello, there!" Tom exclaimed, as if he were just seeing Michael for the first time. As if we had not been sitting and chatting with him only a few minutes before.

Tommy had shared that his father was suffering from memory loss. It was clear that it was severe, maybe Alzheimer's or dementia. But what was more remarkable than the erasure happening before me was that, after his memories were gone, pure delight and friendliness remained. Tom was thrilled to see Michael and would be thrilled again each time he encountered him, as if every moment was the very first.

Beyond the erasure, his memories were gone, pure delight and friendliness remained.

"Hi, Tom!" Michael said, matching his exuberance in words and embrace, hugging him hello again. "You headed back to the memorials? Why don't I go with you?"

And then Tom turned to me, the same sweetness in his face since we had introduced ourselves maybe 30 minutes before.

"Are you living in? Will you be staying for a while?" he asked. And again I said that yes, I was here to live in long term, to which he patted my arm and, with the same beaming, grandfatherly satisfaction as before said, "That's wonderful."

Bishop Ross

Jesuit priest J. K. Kadowaki was a Japanese Christian theologian as well as a student of Omori Sogen, the Rinzai Zen master who co-founded Chozen-ji. In his book, "Zen and the Bible", Kadowaki describes an aging Catholic bishop, Bishop Ross, who spends some time in the Blessed Mother Hospital in Tokyo after a brain hemorrhage leaves him partially paralyzed and unable to speak. Becoming concerned that the bishop was a burden on the hospital, the Jesuit Superior sought to make other arrangements. But when the Sisters at the hospital learned that Bishop Ross might be moved, they begged that he be allowed to stay.

"'This half-paralysed patient who couldn't speak,'" Kadowaki writes, relaying the words of his Jesuit brother, Brother D, "'was exerting a great spiritual influence on a large number of persons. His eyes, bright as a child's, his kind smile and good humour completely captured the hearts of the Sisters and nurses and doctors who cared for him.'"

Later, Kadowaki interprets Brother D's account, both through his own cultural lens and with a Zen commentary on the body–not just a mass of bones, sinew, and blood, but also energy and kiai, or as the Catholics might say, charism:

"He was physically incapacitated and his brain deteriorating, and yet the 'body' of Bishop Ross radiated a lofty spirituality that was capable of touching the hearts of others. No one has demonstrated more admirably how the 'body' speaks with greater eloquence than any words. What the modern Japanese respect most is a high IQ, a good memory, and the ability to act rationally. All of this had been taken away from Bishop Ross, and yet as a human being he was able to teach something extremely valuable to others. Isn't the charismatic figure of the senile Bishop Ross a stringent warning to us modern Japanese?

“He was physically incapacitated and his brain deteriorating, and yet the 'body' of Bishop Ross radiated a lofty spirituality that was capable of touching the hearts of others.”

"When I close my eyes, there floats before them the figure of the aged, cheerful Bishop Ross smiling to a nurse in his room at Blessed Mother Hospital. Then the figure of him enthusiastically teaching Latin in a shabby classroom at Sophia University is superimposed on it, forming a double image that continues, even now, to teach me what it means to live."

Takashi Nakazato

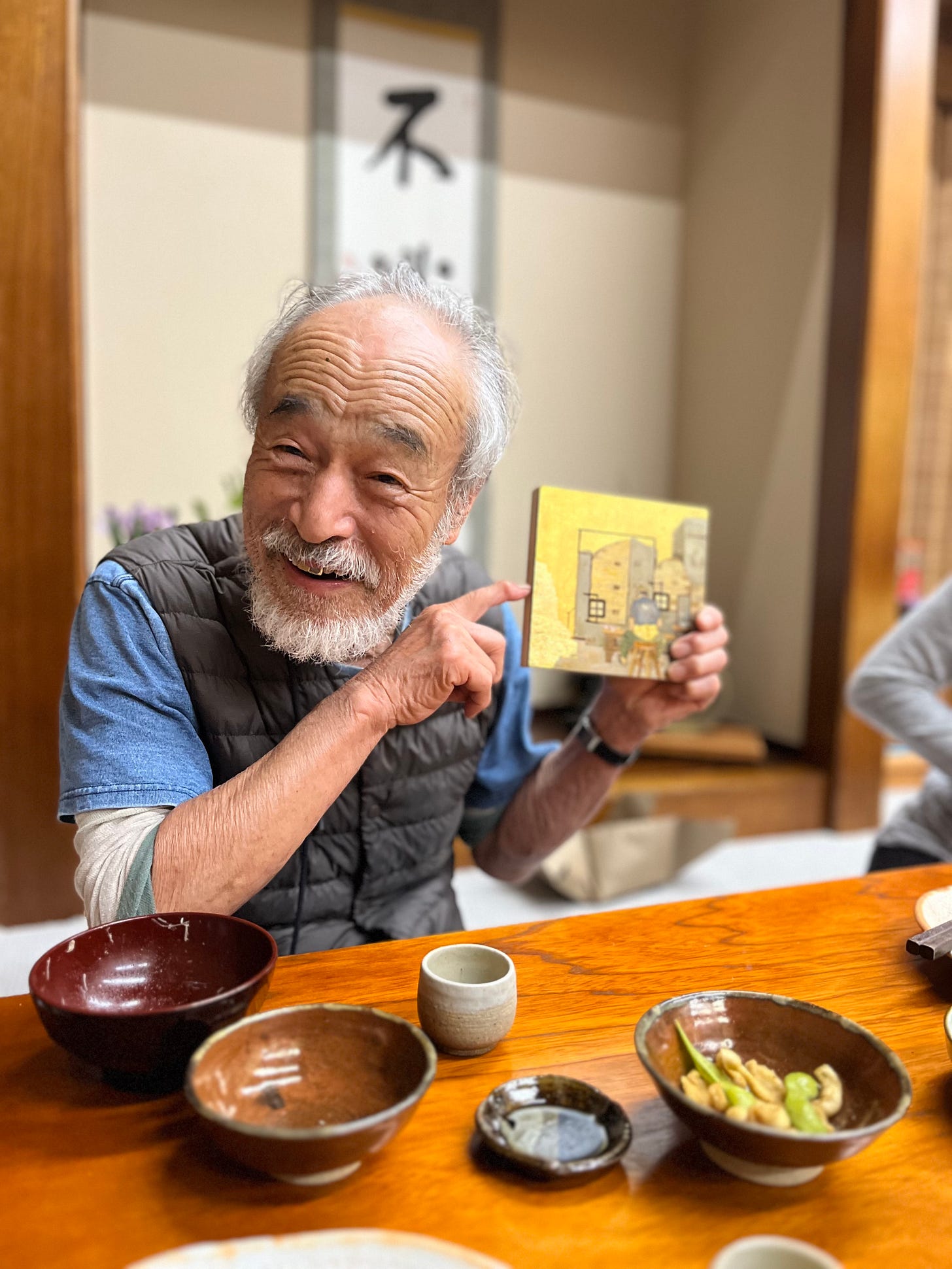

For my last profile, I'd like to introduce Takashi Nakazato, a 13th generation master ceramicist from Kyushu, Japan. His family is the only one remaining that still makes the unique style of ceramics known for the region, Karatsu-yaki, or Karatsu ware. His father, Taroemon Nakazato, was considered a Japanese national treasure.

At 85 years old and having long ago left his ceramics studio to his own son, Takashi Sensei now travels the world making ceramics and teaching workshops. This past December, he made his destination Chozen-ji, our little Zen temple in the back of Kalihi Valley on the island of Oahu.

As his designated temple host and assistant, I stayed close by, watchful for just the moment he might be preparing to wedge a 15-lb hump of clay or pick up a ware board heavily laden with freshly thrown pieces.

"Sensei! Can I wedge that for you?" I would call to him. "Can I carry that for you?"

And each time, he responded with the same smile, saying "thank you" in a way that was, really every single time, disarmingly genuine.

I was shocked by Sensei's industriousness and energy and it made sense to learn that his Chinese zodiac sign is the Year of the Ox. For a full eight hours a day, he would make piece after piece of ceramics. I couldn't prepare clay for him fast enough and raced to reorganize our ware shelves to make room for his new work.

Sensei had never trained in Zen, though he had been interested in Zen philosophy as a young man. He was also unfamiliar with our approach at Chozen-ji of using a variety of martial and fine arts as Dō, or Ways, to train in Zen and perfect Human Being. But yet, the way in which he approached ceramics reflected what we at Chozen-ji would recognize as more than just "pottery" but rather, The Way of Clay.

The way in which Nakazato Sensei approached ceramics reflected what we at Chozen-ji would recognize as more than just "pottery" but rather, The Way of Clay.

"You know Mu Shin?" Sensei asked me while throwing on the wheel one day.

Mu Shin literally translates to Void Mind, though both words in a Zen context have complex and nuanced meanings. Mu does not only mean void or empty; absolute emptiness also encompasses everything. Shin does not just mean mind in the sense of consciousness or a brain, but is more like a compound of three different ways of knowing: Mind-Heart-Spirit.

Yes, I told Sensei, I was familiar with the Zen concept of Mu Shin.

"Make 600 pieces a day," he smiled, his eyes twinkling mischievously, "and Mu Shin."

At that moment, I had just been relaying to another student how, when Takashi Sensei was in his prime, he would work 14 hours and throw 600 pieces a day. When I did the math, taking into account time to eat meals, wedge clay, move ware boards, etc, this meant he must have been making a new piece every minute.

"Make 600 pieces a day," Sensei smiled, his eyes twinkling mischievously, "and Mu Shin."

In my six weeks with Sensei, I came to see how ceramics done his way—fast, rugged, immensely disciplined and yet without attachment—could empty the mind and fill the spirit. And I saw the end results in the nearing perfection of humanity in him.

To date, Takashi Sensei is the happiest and most free person I have ever met. It was common to hear him comment simply, "I am so happy," when surrounded by friendly faces, good wine, and good food. When his pieces cracked or were broken by clumsy hands, he smiled and said without hesitation to go ahead and just recycle them. He would even throw the scraps into the slop bucket with a gleeful howl, just for fun.

When a huge pot he had worked on for a whole week was damaged beyond repair while being placed in the kiln, he squealed with laughter as if to say, "Oops!" But then, seeing how distressed I was, he turned to me, put his hand on my shoulder and said, "I'm sorry." And then he promised that the next time he came to visit, he would make us two giant pieces.

Molded by Zen, the Jesuit path, and the Way of Clay, each of these men arrived at the truest expression of themselves—free, kind, and an indelible twinkle always in their eyes. None of it, I know, came easily or naturally. They only arrived at these end states by working the raw material of their lives, sometimes intentionally through the rigors of spiritual training and at other times just by absorbing fully what there was to learn from life.

They are beacons, demonstrating that it is possible to train ourselves to the point of not necessarily being Enlightened, but pleasant, joyful, and a delight to be around—especially towards the ends of their lives when their faculties have begun to leave them. And, perhaps, that is what true Enlightenment is, taking away others' fear and anxieties and replacing them with a smile.

They are beacons, demonstrating that it is possible to train ourselves to the point of not necessarily being Enlightened, but pleasant, joyful, and a delight to be around—and perhaps, that is what true Enlightenment is.

For myself, I'd rather not wait until I am old and without my faculties to see if I can be kind. I feel fortunate that I have encountered what could be considered a technology in Zen to accelerate the maturing and wisdom that otherwise might have taken a lifetime to learn (if I was lucky). And it may still take a lifetime of training deeply to achieve these men's effortless state.

This only behooves me to dig as deeply as I can now. What this looks like is approaching training as life and life as training, and resolving to always look at myself and how I can change first. The more I do this, I find, the happier and more free I feel; and the brighter the twinkle in my own eyes.

Good to find your writing Cristina. "My premise today is that spiritual training can refine us to the point that we can be kind in this life and bring light to the world as long as we live." Yes! This is what we hope to offer at our temple - bringing folk into relationship with emptiness / fullness, and hopefully all becoming a little kinder in the process. Bowing from here 🙏🏻

"They only arrived at these end states by working the raw material of their lives..." This seems connected to the notion of Keizoku. The older I get the more I realize the adage "use it, or lose it". Yet, in my experience it seems more than just keeping moving to allow your body to remain flexible and fluid, but continual effort or a practice of life as a way to burn everything up and naturally refresh the mind and spirit. I find, in glimpsed moments after training, that my concerns or problems of life have fallen away and I can be more present and embody joy naturally. It seems the folks you describe have found a longer, more sustained way to be--to just be. Thanks for another good read.