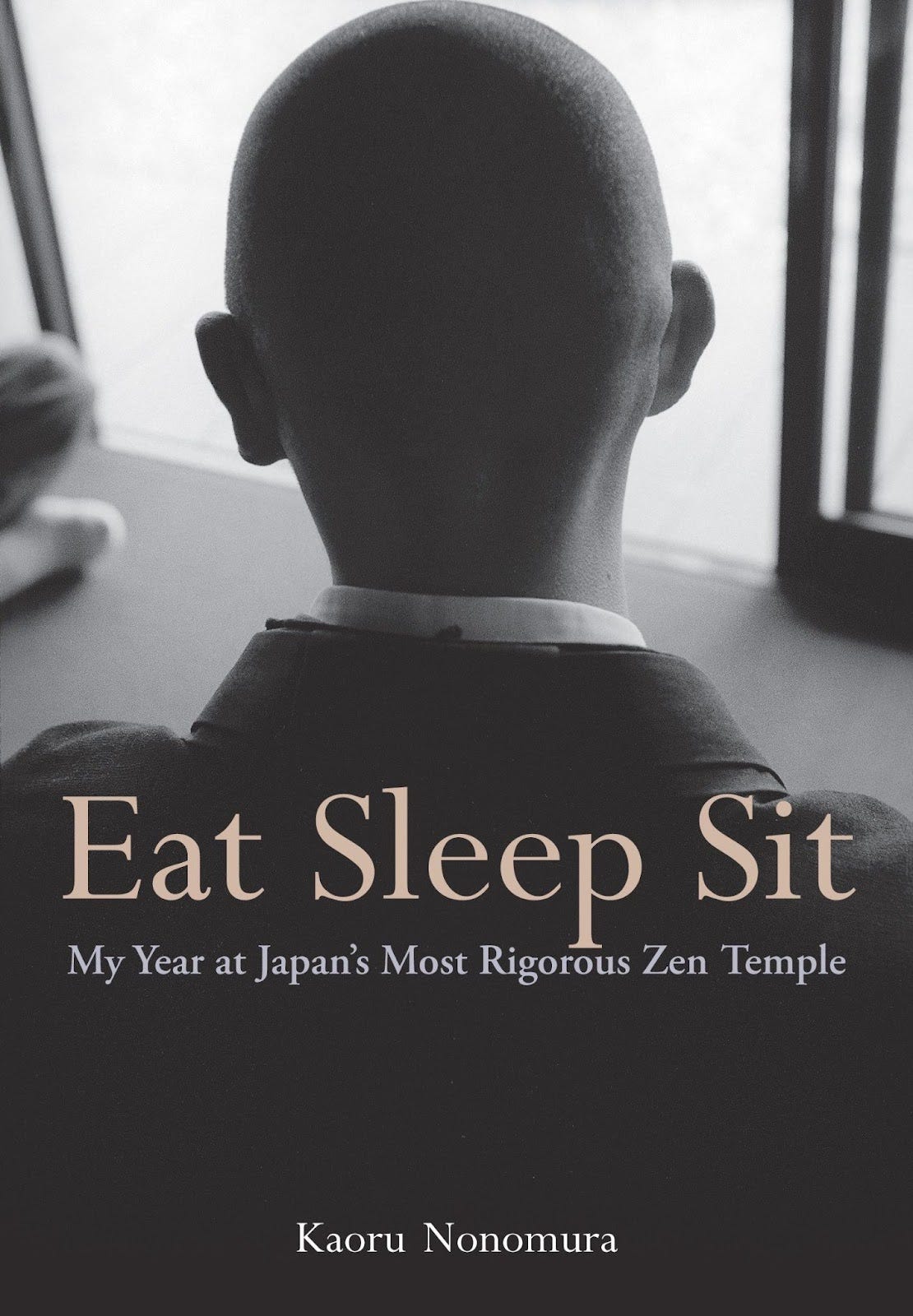

Long Lost Cousins

Finding the familiar in Kaoru Nonomura's memoir of a year at a Japanese Zen temple

Several years ago, I asked a friend to come out to Hawaii to film a short video that would show Chozen-ji's unique approach to Zen training. Getting to see Dojo life behind the scenes surprised him. After several days of following us around from 5AM until 11PM, he finally admitted that we had flipped his understanding of Zen training on its head.

"Cristina," he said. "I know that everyone thinks your guys' life is calm and peaceful because you live at a Zen temple. But honestly, you have the most intense lives of anyone I know."

I remembered this exchange recently while reading Kaoru Nonomura's memoir about living at Eihei-ji, called Eat Sleep Sit: My Year at Japan's Most Rigorous Zen Temple. At turns, Nonomura's memoir is calming and shocking. Life at Eihei-ji reads a lot like Buddhist boot camp, with very meager food, almost no sleep, long hours of zazen, and harsh weather. New monks are berated, hit, slapped, and kicked by the senior monks, who struggle themselves to have to dole out such physical discipline, with still fresh memories of what it was like to be on the receiving end.

As I was finishing Eat Sleep Sit, I shared my impressions with a few other Chozen-ji students. It's always fascinating for us to learn about the Zen monasteries in Japan, comparing what we still do the same in Hawaii and what's changed. In many regards, the world that Eat Sleep Sit describes is very different from Chozen-ji. Here, adjustments have been made to match the intensity of the physical training, local culture, and the temple's aims as a place to train lay people.Though the food is often simple, there's always plenty of it. The only time a student is liable to be hit, kicked, or knocked to the ground is during martial arts training. And here, the Japanese monk's daily black robe has been exchanged for coveralls and martial arts training clothes.

Despite our differences, what remains the same is that the training gives no quarter for the mind and one's habits. This exists to a degree that would be considered unreasonable and even irrational in normal life. In that, when we learn about what Japanese Zen monasteries do to maintain the same rigor and impossibly high standards, it feels like learning about our long lost cousins.

After I described the harsh conditions and the regimented schedule at Eihei-ji, one of the students, who happened to be the one person of Japanese descent from a mixed group of Korean, Mexican, Filipino, Thai, and Chinese folks, asked the book's title.

"It's called Eat Sleep Sit," I said.

"Ha ha!" Her eruption of laughter took me wholly by surprise. "So," she quipped, "it's basically the Japanese version of Eat Pray Love!"

I was stunned and could not, for the life of me, understand what she was thinking.

"Umm, well, six of the guys have already been hospitalized, basically for starvation at this point," I countered.

"So it really IS the Japanese version of Eat, Pray, Love!" She laughed again, even harder.

It took me a while to get the joke. But, eventually, I understood that she was poking fun at the Japanese tendency to be somewhat cold and direct, as well as at Western attachments to self gratification and emotions. Indeed, both books are based on the premises of common, shared cultural understandings about what it means to find oneself. It's just that the Japanese or East Asian versions and the Western version differ starkly. Nonomura's maturation and self development emerges from his complete commitment to life at Eihei-ji, no matter its austerities or severity. Eat Pray Love is about a privileged white woman who jets around the developing world to find meaning (and, lest we forget, love!) while still awash in material wealth, indulgence, and privilege.

I wish that more people who were interested in Zen or coming to train at Chozen-ji would read Eat Sleep Sit. They would have such a clearer picture of what it is that Zen training in a monastic environment has to offer. They would much better understand where the challenges would lie and what we really mean when we say that, if we're doing our jobs, the training is going to make you want to quit.

Eat Pray Love, on the other hand? Definitely not good pre-reading for Zen training. And therein, for a Zen temple in America, lies the rub. Because the American version depicted in Eat Pray Love is what Americans usually think of when they imagine a path of spiritual or self development. It really doesn't matter how hard we try to describe the training and cultural context of Chozen-ji on our website. Eat Pray Love and similar spiritual tropes have made an indelible impression on the Western mind that can be impossible to erase.

The truth is, though, that whatever a person thinks they're going to find in Zen training is often flipped on its head once they encounter the real thing. This also includes any expectations of finding a fully Japanese aesthetic experience at Chozen-ji, since we are so organically of Hawaii. To say that the best advice is to not have any expectations at all may sound trite, a piece of guidance so overused that it's lost real meaning. But that really is the best way to approach it: no expectations and yet, at the same time, totally committed to not quitting, no matter what.

That is, perhaps, the greatest lesson imparted by Nonomura's Eat Sleep Sit, conveyed most of all by the absence of attention it's given. Nonomura barely describes at all the personal circumstances that pushed him to become a Zen monk. The book doesn't start out with existential questions or any crisis of identity. He lets the forms and the methods of the monastery speak for themselves, defined and refined as they have been over hundreds of years to address a timeless human desire for meaning. Even if its outward forms have changed, the fundamental method I see reflected in our long lost cousins still remains intact here in Hawaii, using whatever creative means are available to get people tired enough (in every sense of the word) so that they stand a chance of letting go of their limiting internal narratives, their doubts, and their small, isolated selves.

I loved this book and haven't found anyone that has read it.

I’m going to read it though I come in with a lot of judgment about the physical conditions that sound extreme.